I cannot say enough about Billy Wallace’s piano playing here. It is hard to believe he laid down a performance this good and then had roughly five more credits for the rest of his career. It’s a fascinating style — his right hand is weaving unpredictably through chromatic lines just as adventurous as any horn or brass player’s, and he’s far more willing to allow his left hand to wander than others working in the prevailing style of the time, yet always jolts back to home base just as you question if he’s wandered too far. Upon first listen, I was, briefly, genuinely disappointed by Ray Bryant taking the reins on the final track, if only for the want of more of Wallace’s work. Of course, Bryant does just as good a job at evoking the playful straightforwardness I loved about Richie Powell without coming near being an impersonation.

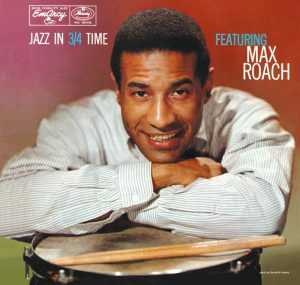

Viewed in the context of Roach’s next move after the loss of Brown and Powell, there’s no finer comparison than to throw on the Rollins rendition of ‘Valse Hot”. At twice the length and a couple notches up in tempo, you see how fully Roach has taken the reins — still finely tuned, but just that much more urgent. The song takes on the energy of one of Roach’s solos, which had always been appealing in their feeling of wanting desperately to burst from the seams of the Roach/Brown quintet’s work, and with the effect being effervescent when they succeeded in doing so. This reconfigured quintet always has a foot hovering over the gas pedal. The additions of Wallace and Dorham subvert any ideas of “replacing” Powell and Brown — Roach’s strategy was to find two players willing to follow his full-steam-ahead lead and find something new. That desire seems to also drive the decision to make an entire album outside the time signature a lot of artists can spend an entire career inside. And the effect, of course, is effervescent: a jaunty detour, a thunderous assault, an honorable continuation, a fresh start.